Laughter in the Fields: A Day with the Children of Torbalı

September 5, 2025 — by Dr. Selin Yıldız Nielsen

On Friday, September 5, 2025, our little caravan—Agenor Mafra Neto, Fatma Juma, Jean-Pierre Princen, Martine Laroye, and I—drove out to Torbalı, where Syrian families live in makeshift tents and bare, improvised shelters ringed by fields of fruit and vegetables. It’s a place where childhood and work share the same dusty ground. Many of the older kids spend long hours picking produce; the younger ones, often barefoot, learn to navigate the world on dirt paths scattered with glass and plastic. Water must be boiled, electricity is “borrowed,” and rent goes to farm owners. The arrangement feels uncomfortably close to indentured servitude.

The Human Migration Institute has been visiting these camps for years—at least four—sending a teacher to give the children a few hours of basic reading, writing, and math each week. People come and go, but a steady community of 30–35 families remains. Recently, when political changes in Syria raised hopes, a few families tried to return. Within days, they phoned back to say, “Don’t come.” No jobs. No infrastructure. No stability. So the tents in Torbalı are still full.

A Line for Hugs

As our car turned onto the familiar dirt road, the children spotted us and ran toward the entrance, shouting and waving. We brought pastels and drawing pads—one for each child—plus juice, cookies, and a ball. Before we could unpack, a handful of kids had arranged themselves into a hug line (no one told them to; they just did it). One by one they squeezed us tightly—some quick, some lingering, some hopping on one foot while waiting their turn—then darted off to play.

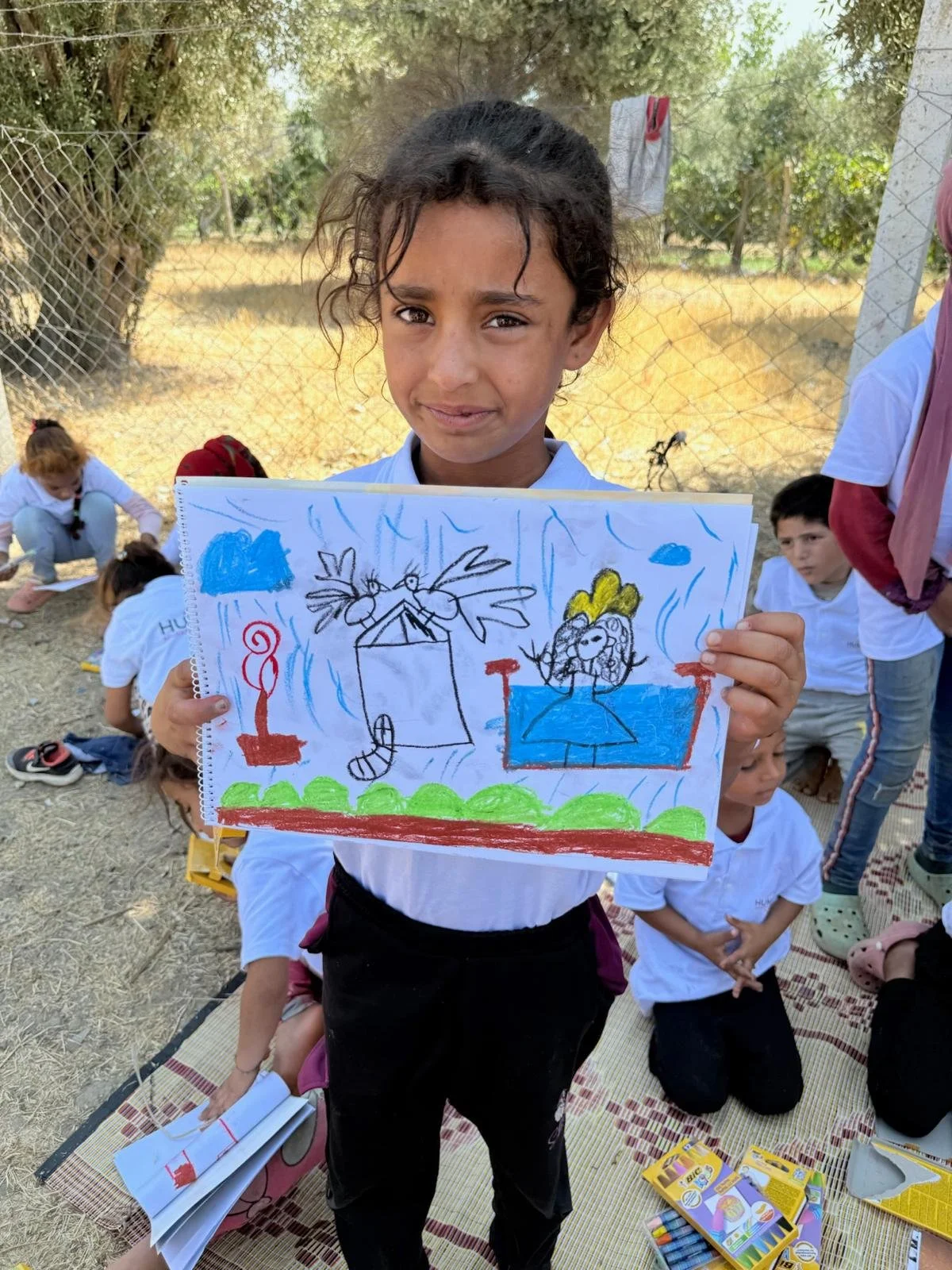

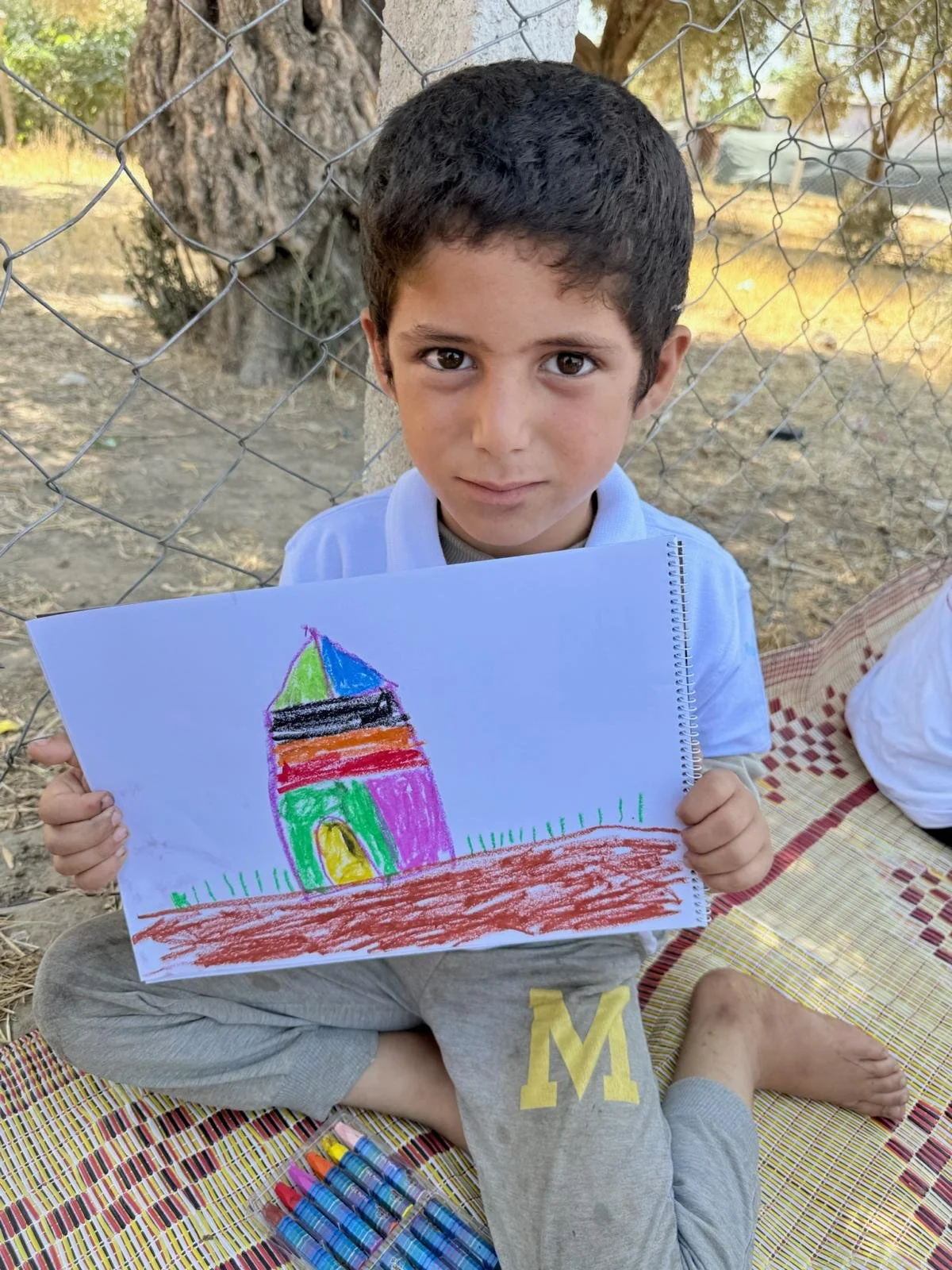

We set up a little art corner on an old tarp. Some kids immediately got serious, heads bent over their paper like tiny architects; others treated the pastels like new toys they had to test from every angle. Several took turns doing cartwheels and handstands—one boy landed a perfect handstand, froze for a second, and toppled over laughing so hard his friend fell over too. Laughter is very contagious in Torbalı.

Fatma’s Welcome Committee

Fatma Juma, HMI’s community liaison, is Syrian originally and a college student in Istanbul. She speaks Arabic with a gentleness that makes kids beam. The moment she stepped out of the car, a little welcome committee formed around her. “Fatma! Fatma!” they called, tugging at her sleeves to show drawings and scrapes and stories. She translated parents’ questions, soothed a toddler who’d fallen, and—somehow—kept a game of catch going while explaining which families had recently moved.

When one shy girl hesitated to join the art circle, Fatma sat beside her and began drawing a tiny window and a tiny door. The girl added a roof, then a tree, and before long two more kids scooted over to help—a house built together, line by line. The children don’t just know Fatma; they trust her. Her presence turns visits into community.

A Boy and a Toddler

There was a boy—maybe ten—who never left the side of a toddler he was caring for. When we passed out juice and cookies, he handed his share to the little one without hesitating. It was hot. Everyone was hungry. He simply gave it away and sat down beside the toddler, entertaining him with a bottle cap and a story told in gestures. He didn’t ask for more. That quiet, sturdy kindness carried me through the rest of the day.

The Girl with Red “Nail Polish”

Agenor spent time photographing the children’s drawings (with permission). At one point he noticed a very small girl, five or six, whose drawing pad was still blank. He crouched down to see if she needed help. She looked up, eyes sparkling, and lifted her hand—she’d been painting her nails with a red pastel. Ten tiny crimson nails. A masterpiece. She studied them like a fashion editor and declared herself ready for the runway.

The House in Her Heart

Later, a minibus rolled in from the fields—teens and young parents returning from work, shoulders dusty, faces brightening at the sight of their children. A girl stepped out who looked about twelve. I recognized her from a few years back—then, a bubbly child who loved to race the boys to the ball. Now her face had changed. Not unhappy, exactly—just older, responsible. She watched the little ones crowd around the crayons with a look I can only describe as longing.

“Would you like a set too?” I asked softly. She nodded with the seriousness of someone accepting a contract. I handed her a sketch pad and a small box of pastels. She slipped into her family’s tent—privacy matters at that age—and started to draw. When I peeked in, she turned her paper toward me: a house with a garden. Later, when we laid the drawings together, I noticed the pattern—so many houses, so many gardens. Not a single child there lives in one.

A Spider and a Song

Our French friends joined us with grocery store cards and school supplies. Martine sat with a toddler and taught him a nursery rhyme with hand motions about a little spider. He watched her mouth intently—he didn’t know the language—but he could feel the rhythm, the melody, the joy. He tried the hand motions himself, eyes wide with concentration, then burst into giggles when he nailed it on the second try. In that tiny circle of music and mimicry, language wasn’t a barrier; it was a bridge.

What We Carry Home

We always leave Torbalı carrying more than we brought. The children have so little: no shoes, few clothes, no toys. But the way they share—a cookie, a crayon, a hug—is an education in humanity. They invent games out of bottle caps. They make teams without adult referees. They look after one another like siblings. They have learned social life by practicing it, and somehow the result is gentleness.

As the sun began to dip, we packed up. A few kids carefully slid their drawings into plastic sleeves we’d brought, smoothing the edges like precious documents. One boy asked if we’d return next week. “Soon,” I said. He nodded like a project manager, satisfied the timeline had been set.

What Comes Next (How You Can Help)

HMI is committed to deeper, steadier support. Our partners at IBC have promised a container we can convert into a classroom—a dry, bright space where children can learn out of the rain and wind. We’re also reaching out to local Rotary Clubs and community allies to help make it a safe, welcoming place with shelves, mats, light, and a door that closes.

Here’s what would help right now:

Container classroom build-out. Insulation, flooring, shelving, tables, a whiteboard, and a door lock for safety.

Shoes & clothing. Durable children’s shoes (toddler to teen), socks, and clean, season-appropriate clothing.

Learning supplies. Workbooks in Arabic and Turkish, early readers, notebooks, sharpeners, pencils, crayons/pastels, and a simple printer.

Healthy snacks & clean water support. Long-life milk, nuts, dried fruit, and support for safe water storage/boiling equipment.

Outdoor play & shade. A canopy or two, a few soccer balls, jump ropes, and sturdy mats—small things that make big joy.

Monthly teacher stipend. Consistent pay keeps instruction reliable.

Community liaison stipend (Fatma Juma). Fatma’s language skills, trust with families, and cultural fluency are essential. A modest monthly stipend will let her continue regular visits, coordinate families, translate, and ensure the classroom is full and functioning.

If you’re able to contribute funds, supplies, or connections (Rotary, schools, businesses, faith groups), we’d be grateful to hear from you. If you can sponsor a monthly basket—for education, snacks, or shoes—or help us equip the container classroom, that would be transformative.

Most of all, keep these children in mind. Remember the boy who gave up his snack without thinking, the girl who quietly drew a house with a garden, the toddler who learned a spider dance from a woman speaking a language he didn’t know—yet somehow understood. They have almost nothing, and yet they meet us with laughter and trust.

Let’s meet them with something sturdier: a classroom, a teacher, and Fatma at the door—welcoming them in, week after week.

With gratitude,

Selin