From Fields to Classrooms: Nurturing Dreams in Torbalı's Syrian Refugee Community

Background

In the province of Izmir, Türkiye, there’s a district called Torbalı, known best for its bountiful agricultural farmlands. At this time of year, tomatoes and grapes are in high season, and soon olives, corn, leeks, mandarins, and plums will be ready for harvest. Just an hour outside of the big city, an exit off the highway takes you winding down a road with minimal signage, descending into a neighborhood engulfed in vast fields of green. Here, you may pass men in tractors puffing cigarettes and groups of children chasing a ball on the side of the road. Life in Torbalı remains bustling despite the scorching August sun. In this quarter, local Turks, migrants from Eastern Türkiye, and Syrians who fled the war, all live amongst each other, sustaining their livelihoods through the productivity of the fertile lands. Though subject to low wages and difficult labor, many of the children in this town are able to receive an education and explore careers in their future.

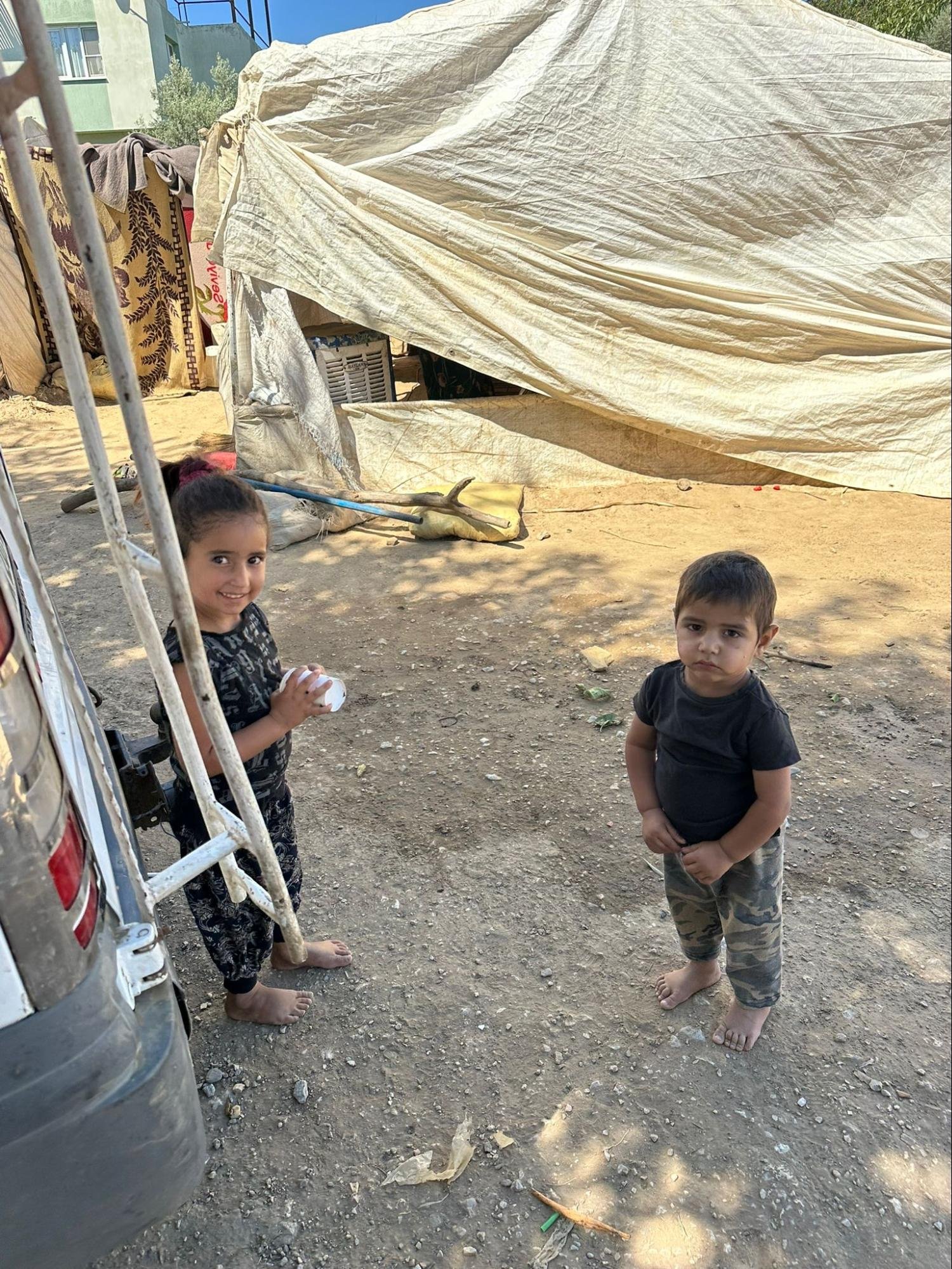

Drive a little past this neighborhood, though, and the story becomes different. The reality of life for the Syrian community in Torbalı is much more bleak, as their existence is largely swept under the rug. Just outside the main town center, a population of over 200 Syrian refugees live in informal settlement communities, unrecognized by the local Turkish governing authority. Many of them risked their lives to come to Türkiye in search of safety and survival, traveling to Torbalı to seize opportunities in the agricultural sector. Yet, the business has not proven to be as lucrative as they had once imagined, and affording basic necessities has proven to be a grave challenge. In order to live in these settlements, each refugee family must pay a hefty price in relation to their wages of around 2000 TL per month, to a landowner who is simultaneously in charge of employing much of the refugee community in his farmlands. Despite paying such a high rent, refugees receive little to no amenities and depend on the landowner for electricity and water needs, which barely satisfy the bare minimum to sustain life.

In this area, there are over ten camps, home to thirty to thirty-eight families, though there is no official public record keeping track of numbers. As pictured above, the refugee community resides in a mix of decaying tarp and brick buildings with no doors or any kind of insulation built to withstand extreme weather conditions. The lack of upkeep and maintenance in the settlement homes begs the question of what the exorbitant rent prices may be going towards.

Besides the problem of inadequate housing, though, a greater issue is plaguing the Torbalı community — lack of education. Since COVID-19, none of the refugee children have been able to attend the local schools.

At HMI, one of our fundamental tenets is our commitment to education as empowerment. Thus, our interest in engaging with the Syrian refugee community in Torbalı initially began out of concern for their lack of access to schooling. Prior to the pandemic, we had succeeded in registering many of the children to attend school in the culmination of a three year effort, even securing a Pitkes grant which allowed us to equip the community with supplies, shoes, and transportation to support their educational needs. But, while these needs were met, several other obstacles arose. Once the children arrived in the classrooms, many of them were bullied by their classmates and faced difficulties adapting to a classroom setting. Several children lacked proper toilet training or experience of how to behave in a classroom, crying and hitting when they could not express themselves to their teachers. Teachers could not easily adapt to their presence, unable to communicate with the children in their Arabic language and attend to the collective needs of the entire classroom.

Dr. Nielsen is pictured alongside Ahmad bey and his wife Fatma, in front of the cow farm Ahmad bey operates and the building in which they sometimes stay.

Providing access to transportation also came with its challenges, as many of the children ran into trouble finding their way home from school, getting lost with no clue which shuttles to take. In one instance, a child got lost for almost twenty hours before she was found alone near a field. These safety risks not only created fear in the children, but also made their parents hesitant to send their children to and from school. Since the children enrolled in school were all younger than ten years of age, they could not be accompanied by their older siblings or parents who had to work in the fields during the day. Older children had virtually no time or energy left to devote to their education as their need to support their families took precedent.

Given the multifarious hurdles blocking educational attainment in Torbalı, it became evident that regular visits to the community itself would be necessary to grasp the specific needs and interests of residents to come up with sustainable solutions. Before embarking on our journey, we planned a budget for stationery, educational supplies, and grocery store gift cards, and asked for funding by bridging our local circles in the United States and abroad to the cause in Torbalı, Izmir. Subsequently, we outlined a three-day program schedule of engaging activities designed to spark scholastic interest, and ultimately set out as a team of five volunteers- Dr. Nielsen (our founder), Melis, Fatma, Beyan, and I (Derya)- to visit the settlement.

On each day, we were accompanied by Ahmad bey, who had previously lived in one of the settlements, and who continues to devote time and energy into giving back to the community. Dr. Nielsen had formed an amicable friendship with Ahmad bey through Muhammad, who works for the Syrian Solidarity Network in Izmir (ISMDD), meeting with them both on her regular visits to the area since 2017. Since he left the settlement, Ahmad has been running a cow farm, owned by the landowner, where he produces meat to be sold in the local markets. Back in Syria, he was employed as a teacher; thus, he was gradually able to pick up the Turkish language, which ultimately allowed him to pursue a life for himself and his family outside of the settlement. Now, some of his children work in an auto-body shop and others work in the fields after school. They must work to survive, but Ahmad stresses the importance of putting education first.

Ahmad believes wholeheartedly in the power of schooling, going so far as to state “egitim yemekten daha önemli”, or in other words, education is more important than food. While immediate needs of nourishment are evidently vital, acquiring literacy and learning a new language provide a lifeline for a brighter future.

2. The Visit

Day 1

As we picked up Ahmad bey from his home on the morning of our first day in Torbalı, we decided to do a field visit of the settlement, to have a chance to meet many of the residents and assess their needs. On our way there, Ahmad bey pointed out the truckloads of tomatoes being harvested by Syrian refugee workers. He explained that some of the newer machinery posed a growing threat to the existence of these laborers. With increasing automation, Ahmad bey fears many of these agricultural jobs will become obsolete. Lacking the skills needed to adapt to the changes, these workers may struggle to find work, especially since they have not acquired basic competencies like literacy.

After a ride through a narrow road passing several Syrian settlements, we arrived at the one Ahmad had previously lived in, greeted by a friendly goat and a crowd of smiling children. Dr. Nielsen had printed out many of the childrens’ photographs taken on her last visit, so we brought along their portraits and group photos with picture frames to distribute. All of the children rushed into the room and sat on the rug, huddled around the photos, searching for their friends’ and their own faces.

Children and adults admire their newly printed and framed photographs together.

Pictured here is Yaz, along with her children, who was kind enough to let us sit in the room for which she pays rent. She had an aura of a leader, appearing to be the unspoken matriarch of the community.

After the excitement of sharing portraits, we gradually wandered outside, where several other children came out to play. Hyper and full of laughs, they climbed the olive trees and jumped from place to place, coming up with creative games that maximized the use of their surroundings. As they ran around the sharp gravel, they created clouds of dust and dirt, yearning to explore and expand their playful activities despite having never stepped foot on a playground.

As our first day came to a close, we had gotten a better idea of the number and ages of children in order to gauge what kinds of activities to have prepared for the next two days. Accordingly, we stocked up.

Most of the children were entirely barefoot, whilst some had shoes torn and worn out from overuse, signifying a grave need for adequate footwear.

Day 2

On the second day, after picking up Ahmad bey again, we stopped by a local stationary store, gathering the following materials: three balls (two soccer and one volleyball), paints, notepads, markers, crayons, wet wipes, a dry erase board, and dry erase markers. The shopkeepers were happy to offer us a few coloring books free of charge to contribute to our cause. We then stopped at a grocery store to pick up some petit-beurre biscuits and juice boxes, and continued to the settlement.

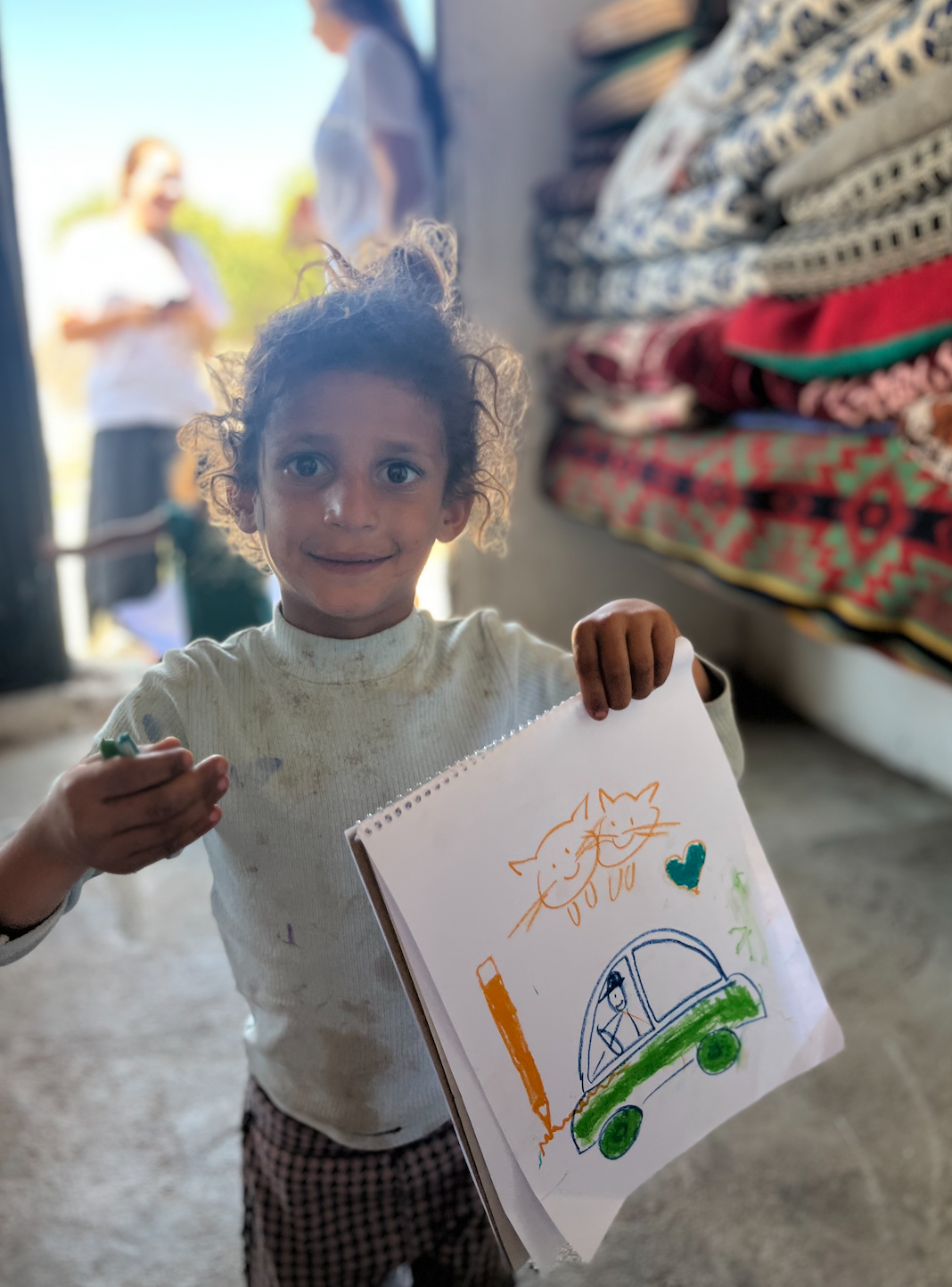

On this day we set up in a smaller room, creating a couple separate stations to split up the activities of origami, building blocks, and face painting. Though challenging at first to calm the childrens’ excitement to focus on the tasks, they gradually took to the activities and found interest in the various exercises.

Here, we showed the children how to make “tuzluk”, which translates to salt shaker in English. It is a customizable paper-made fortune teller to play with friends, which reinforces counting to discover one’s fortune. We showed the children how to write some numbers and draw some images onto the origami paper, and fold it to create the designated shape, giving them a chance to play amongst each other. We also showed them how to fold paper airplanes, and origami boats, cranes, and dogs, teaching them the Turkish words for the animals and objects we created together.

Some children were more interested in building, so they spent some time with the blocks, making creative structures. Other younger children wanted to do face paint and they interacted with each other by drawing shapes and colorful motifs on each other. We made sure to wipe off any paint smudges and helped braid some of the childrens’ hair who had asked for it.

Later, while some of the younger children rested in the shade to do some more calm coloring, the rest of the children went outside to play with the balls, first playing catch in two separate teams, and then, and then a game of soccer.

Afterwards, the HMI team put on music from the speaker and the children all began to dance. We formed a circle holding hands and spinning and then we formed a conga line. Many of the children were exhilarated to be spun around, lifted up and tossed up into the air. We finished by playing a game of “kör ebe”, or tag with a blindfold, and handed out snacks, bringing us to the end of our second day.

Day 3

On the third day, after picking up Ahmad bey again, we headed to BIM grocery store, where we purchased gift cards for each family to use towards their specific needs. We also bought more juice boxes and çokoprens cookies, a favorite among Turkish children. For Yaz, we brought some extra snacks in hopes that she would extend her air conditioned home with us for one last day.

Once we arrived, one by one, we handed each child a notepad and a crayon, so they may begin to draw and write. Some of the fathers sat beside, joining in the excitement whilst enjoying a cup of tea with Ahmad. Letting their imaginations run wild, we saw as the children made up stories and drew fantastical images. Then, we taught them the Turkish alphabet and showed them how to spell out their names, which they were very happy to accomplish.

Outside, a separate group of men were sitting on a rug, chatting and smoking a hookah. They appeared to be on break, so they graciously agreed to give a short interview to Beyan and I.

Here is how our conversation went:

“Can you describe your route to Torbalı? How long have you been at this settlement?”

“We come from Idlib, when we first arrived in Turkiye we came to Urfa, when the camps closed we came to Konya, finally we ended up here. We have been in Torbali for roughly 7 years now.”

“What do you think are your greatest needs at this moment?”

“We are in need of schooling for our children. Education is our number one priority at this moment.”

“Are any of the children taking classes now?”

“Sometimes Ahmad bey comes and gives classes to the children, but it is very infrequent. We are hoping to empty out one of the rooms to create a classroom so he can begin to teach our children more regularly.”

“How do you feel about sending your children to the local school?”

“We don’t want to send our children to the city; it is very far and they are so small, we think they may run into trouble and face difficulties.”

“How has your experience been working whilst living in the settlement? Do you work in the fields?”

“Yes, we help produce tomatoes, leeks, and many different crops. For a work day of eight hours, we make 400 TL. If we think we will be able to finish all of the work, we tell the landowner and receive our wages accordingly.”

“Now, all of the older children are working, they often come home very late as they work until they finish filling up the truck which can last into the night.”

“Since they’re gone most of the day, there’s greater hope for the younger children to learn Turkish and become literate.”

Based on this conversation, it is clear the parents are determined to educate their children. This prime concern of paving a bright future for their children seems to trump all of their other immediate needs of shelter and clothing. In order to make a lasting impact, we will need to address this issue first and foremost.

3. Takeaways & Next Steps

Taking into account community wishes, HMI is proposing to incorporate a classroom in the settlement, which will aim to tackle issues associated with transportation and assimilation into local Turkish schools by bringing education right to their abodes. One resident has already graciously agreed to lend his room to be used as a classroom, and Ahmad bey has offered his expertise to serve as their teacher. In the classroom, funds will need to be allocated for walls to be painted, floors to be covered, windows to be fixed with iron and glass, and cabinets to be installed. Superbox portable wifi units, costing around $200 per device ($30/month for 10-20 gb of internet), may be purchased; additional needs such as books, school supplies, and funds for weekend activities like visiting museums and parks may also be supplemented.

While it may seem small to build a single classroom given the grand scheme of issues faced by this community, we at HMI believe that locally targeted actions can transform into much larger, meaningful change, having massive ripple effects. With success, one classroom can inspire the opening of another classroom in a separate settlement, gradually disseminating across the entire area; and once a single cohort of students gain literacy, they may continue to pass down their knowledge to future generations, and so on. With the support of our donors, we look forward to expanding our role in providing educational opportunities to the Syrian refugee community in Torbali, and hope we may be able to help them reach their full potential.